Why You Must Avoid A SAD Diet

Why is the SAD diet so bad…most of us eat it everyday!

Between work, school, family, and social life our increasingly busy schedules have favored convenient foods that can quickly satisfy our cravings.

In this article Dr. Irina Chan, ND, discusses the research around why you should avoid a SAD type diet. Especially if you are concerned about elevating your risk for cancer.

Maybe we can all relate here. It’s become increasingly difficult to make healthy and nutritious meals all the time. Overtime, we have lost touch with where food comes from and how it’s prepared with the introduction and rise of food processing and widespread distribution, preserved and packaged foods, microwavable meals, drive-thrus, food delivery services, and convenience stores.

It’s important to recognize that it’s not simply a matter of individual choices, but a more complex issue that involves government bodies, societal pressures, businesses, and corporations leading us to eat this way.

We are seeing that over time, fresh and perishable food items have become less accessible and less affordable, meaning that for a lot of people eating healthy every day is not a practical option. Meanwhile, we’re seeing that junk food has become more widely available, more affordable, and very intensely marketed, especially towards lower income communities and children.

The SAD diet or the Standard American Diet (I guess we could call this the Standard Canadian Diet too), is a modern-day diet that has been attributed to poor health.

Some of the issues I have with the standard American diet is that it’s highly processed. The more a food is processed, the less nutrients the food will have. Highly processed foods can literally end up with no nutritional value and cause your body more harm than good.

It’s also pro-inflammatory, meaning that it promotes inflammation in our bodies. Chronic inflammation can damage healthy cells, tissues, and organs over time. Chronic inflammation contributes to a wide range of disease including heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, cancer, obesity, asthma and dementia.

The SAD diet often consists of artificial colorings, which in high amounts can be toxic to the liver as well as other organs. Artificial food dyes may also contain contaminants such as benzidine, 4-amino-bipheny, and p-cresidine that are known cancer-causing substances. Artificial food dyes are associated with hypersensitivity reactions, changes in behavior, mood, concentration, and headaches in humans and tumor formation in rats.

High glycemic foods such as white bread, pasta, sodas, and desserts are low in fiber and high in sugar. This means that when ingested, they are rapidly digested, absorbed through the intestines, and can cause significant spikes in blood sugar. Over time, this can lead to poor blood sugar control and diabetes.

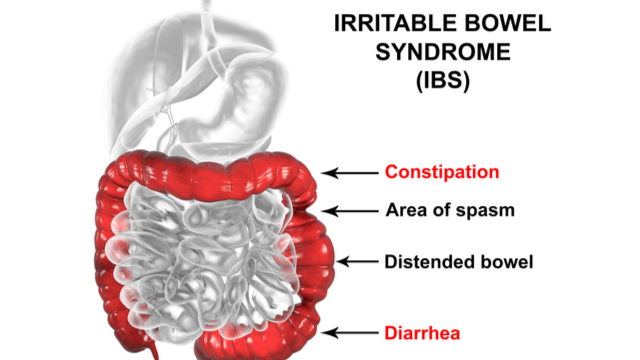

On average, American adults eat 10-15 grams of total fiber a day which is far off from the recommended 25 grams of fiber per day for women and 38 grams of fiber per day for men. Lack of fiber in our diets can promote poor blood sugar control, elevated cholesterol levels, and poor digestive health. A diet high in fiber helps to increase the composition and diversity of our gut microbiome, which enhances our immune response to pathogens and cancerous cells.

Pesticides, which are widely used in agriculture, and hormones, which are often added to animal feed, can be toxic to humans. Pesticides are known endocrine-disruptors and is associated with elevated rates of breast cancer. Furthermore, pesticide exposure during pregnancy is associated with increased rates of leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and brain tumor in children.

On average, Americans eat more than 3400 milligrams of sodium per day. However, the recommended daily limit for sodium intake is less than 2300 milligrams or approximately 1 teaspoon of table salt per day. Diets high in salt is associated with elevated risk of developing high blood pressure, which is a major cause of stroke and heart disease.

And lastly, the SAD diet is often high in trans-fat and saturated fats, which can lead to inflammation and obesity. It can also lead to buildup of fatty deposits in our blood vessels and the development of coronary artery disease, putting one at risk for heart attacks and strokes.

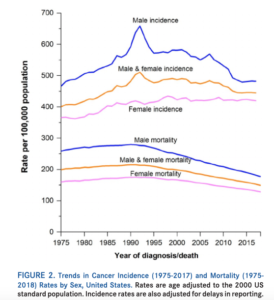

The graph shown here depicts the rate of cancer incidence and mortality between 1975 to 2018. Between 1975 to approximately 2000 there has been an increase in cancer incidence and mortality in both men and female. This upward trend has been linked to the increased intake of unhealthy fats, cholesterol, and refined sugar.

You will also notice a decrease in rates after approximately 1995. This is most likely due to increased cancer surveillance, advancements in cancer treatments, and cancer prevention programs focused on nutrition, physical activity, and other modifiable risk factors.

Now let’s get into the research involving the cancer risks with certain foods we are consuming.

Studies looking at the incidence of cancer in those who consumed the highest amount of red meat versus those who consumed the lowest amounts had a 9% increased risk of breast cancer, 10% increased risk of colorectal cancer, 26% increased risk of lung cancer, and 22% increased risk of liver cancer.

Similarly, studies looking at the incidence of cancer in those who consumed the highest amount of processed meat versus those who consumed the lowest amounts had a 6% increased risk of breast cancer, 18% increased risk of colorectal cancer, 12% increased risk of lung cancer, and 24% increased risk of stomach cancer.

There is a 12% increased risk of cancer associated with sugar-sweetened beverages like soda and juice. Moreover, consuming high glycemic foods (foods that are high in sugar and low in fiber) can contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes which has been strongly linked to increased risk cancer including cancer of the bladder, breast, colorectum, endometrium, kidney, liver, and pancreas.

In addition, high amounts of dietary salt intake have been shown to increase risk of stomach cancer and esophageal cancer.

Before we end this article, I want to touch on obesity.

Recent work has revealed that overweight or obesity, as measured by weight or body mass index, does not increase cancer risk; rather excess visceral adiposity or the fat that covers our organs, as measured by waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, is.

Specifically, abdominal obesity is associated with a 42% increased risk of colorectal cancer, 32% increased risk lung cancer, and 6% increased risk of post-menopausal breast cancer.

Researchers looked at women diagnosed with breast cancer and followed them for 9 years. They found that compared to women who were able to maintain a stable weight, those who gained a median weight of 6 pounds after their breast cancer diagnosis was associated with a 35% increased risk of death from breast cancer. And those who gained more than 17 pounds had a 64% increased risk of death from breast cancer.

Similarly, compared to men who were able to maintain a stable weight, those who gained more than 4 pounds had twice the risk of prostate cancer recurrence.

From such studies we can extrapolate the importance of maintaining a healthy body weight to prevent the development and recurrence of cancer.

There are many health risks associated with the SAD diet, especially when it comes to cancer. While I know how hard it is to change habits, especially when it comes to eating, I think it’s important to try.

There are many healthy ways of eating to choose from. Pick one that suits your lifestyle and start making small changes towards a healthier you!

If you have any questions about your health, cancer prevention, or integrative cancer care, you can always book a free consultation with Dr. Irina Chan, ND by clicking here.

References:

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21708

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34455534/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33854607/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34957192/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31995192/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29026008/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27983672/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27432212/